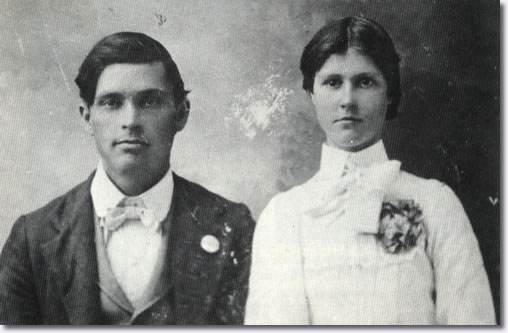

Elvis Presley's Grandparents

Copyright by EP Music 1996-2009

Copyright by EP Music 1996-2009

I'd like to say there was never a harsh word between David and me. If I was slightly sentimental, I would. It might even be true, like certain brain-dead remarks: Kids are great! and Puppies are a handful! We never fought, he and I, but we had our moments, you might say. He worried about my boyfriends and my wild-child ways; I worried about his career, his health, and what I privately thought of as his silliness.

He was certainly the smartest guy at the Iowa School of Art and Art History, but he dawdled over his MA thesis on Samuel Palmer, then abandoned it, saying, But everyone's written better stuff than I ever could. When I wound up in Texas, teaching 18th c. visionary art, as I'd grub for Samuel Palmer-factoids, I'd think, goddamn it, David, because, in fact, no one had written anything better. He wouldn't go into Iowa's art history doctoral program either, but neither would I. He smoked too much, didn't get enough sleep, and stayed up late reading, but I was the same way, and we kept each other company during those endless insomniac nights.

Still, he had massive grand mal seizures, took heavy sedatives for them, and, against all Iowa vehicle laws, he drove. For him, a car was more necessary than breath. One winter, finally, he had a seizure on any icy road, wrecked his car, and banged himself up. Afterwards, I waited in the hospital, along with his brother, the two of us slumped in bright yellow plastic chairs, silently staring at our knees, scared to death. But David was okay.

His silliness, as I called it, was any uncharted Davidness I didn't get: his weird asshole roommate, his lack of a companion, the part-time teaching job at Coe and, later, his thirty year residence in the same apartment. But whenever I'd mention any of it, he brushed me off as benignly as a wayward ant.

His lack of a companion was something I almost understood. David was profoundly, deeply solitary. He was effortlessly charming, knew many more people than I did, and liked them all but, ultimately, he delighted in being alone. I liked being alone myself, and was always swapping out one boyfriend or another, trying to find a guy who'd put up with my sudden absences. But I was also in the throes of ending one long marriage and, not much later, would marry again. "Being alone is the ultimate existential position," David argued, when I told him about my plans. "Seeing another person's toothpaste in the sink is pretty existential too," I said. That we used the word existential about such things tells you how young we were, not long out of school.

I couldn't crack the weird-roommate-riddle though. Not for a long while. Ken, as we'll call him, was a narcissistic artist, with more compulsions than toes, who shared David's large apartment for three years, in a moldering Victorian mansion. Each morning, sitting bolt upright in bed, he loudly recited his latest dream into a video cam. The furniture was arranged in a nutty shin-scraping fashion, because Ken believed that furniture wanted to be in certain places. Whenever I stopped by the apartment, one of Ken's many depressed girls was always in the kitchen, moodily eating cornflakes, dressed in one of his t-shirts. They came and they went, these girls, and I never knew their names.

Ken was a performance artist, one who ran around on all fours, mimicking animal movement, wearing a black stretch suit, using self-invented shock absorbers so he could lope along easily, like a dog or coyote. He nagged David into photographing him outdoors, doing his thing, which David hated but always acquiesced. Inevitably, a fearful passerby would call the police to report a huge black ape loose on the streets. When the squad cars came, Ken refused to say anything. He'd just trot around aimlessly on all fours, while David tried to explain performance art to a bunch of cops.

Eventually, Ken disappeared into a Bowery studio, where he may be to this day, for all I know. For years, David maintained a near saintly patience with Ken's vagaries just because he liked him. At least that's what I believe because it's so David-like. It may even be true.

The closest David and I ever came to a fight was ten years ago. Just wanting to hear his voice, with its welcome flat Pennsylvania accent, I called. We chatted about this and that, innocuously I thought, and then David asked very quickly, "So how does it feel to be a corporate sell-out?" There was real anger in his voice, an anger I'd never ever heard, and I was speechless, then felt a dangerous hot answering anger in myself.

But the better angel of my nature, a smallish angel to be sure, recognized the innocence in his question. David didn't know squat about global business and why should he? Gently, unlike me, I explained I'd wanted to know how consumer products got dreamed up, created,and manufactured. I'd been curious and went adventuring and that was all. "Oh," David said, his voice lifting with something like surprise. And then we were okay.

Later I thought how old friends become our parents if we don't watch out. Bewildered by our later choices, they wonder out loud, But the man you divorced was so perfect. And then you threw away your whole career, moving to that crime-ridden city?

Exasperated, you want to smack them in the head. That man I divorced was crazy, my career was a big zero, and my home town was a cracked-out Springsteen rust belt.

Your friends' questions are as unanswerable as those of aging parents, shouted over too a far distance. But like our mothers and fathers, our old friends are only asking, Do you remember me?

Sometimes, we can holler back, loudly and truthfully: Yes! Yes! I see you! I see you as you were. I see you as you are. I loved you then. I love you now.

If we're lucky, lucky dogs, that's what we can say.

He was certainly the smartest guy at the Iowa School of Art and Art History, but he dawdled over his MA thesis on Samuel Palmer, then abandoned it, saying, But everyone's written better stuff than I ever could. When I wound up in Texas, teaching 18th c. visionary art, as I'd grub for Samuel Palmer-factoids, I'd think, goddamn it, David, because, in fact, no one had written anything better. He wouldn't go into Iowa's art history doctoral program either, but neither would I. He smoked too much, didn't get enough sleep, and stayed up late reading, but I was the same way, and we kept each other company during those endless insomniac nights.

Still, he had massive grand mal seizures, took heavy sedatives for them, and, against all Iowa vehicle laws, he drove. For him, a car was more necessary than breath. One winter, finally, he had a seizure on any icy road, wrecked his car, and banged himself up. Afterwards, I waited in the hospital, along with his brother, the two of us slumped in bright yellow plastic chairs, silently staring at our knees, scared to death. But David was okay.

His silliness, as I called it, was any uncharted Davidness I didn't get: his weird asshole roommate, his lack of a companion, the part-time teaching job at Coe and, later, his thirty year residence in the same apartment. But whenever I'd mention any of it, he brushed me off as benignly as a wayward ant.

His lack of a companion was something I almost understood. David was profoundly, deeply solitary. He was effortlessly charming, knew many more people than I did, and liked them all but, ultimately, he delighted in being alone. I liked being alone myself, and was always swapping out one boyfriend or another, trying to find a guy who'd put up with my sudden absences. But I was also in the throes of ending one long marriage and, not much later, would marry again. "Being alone is the ultimate existential position," David argued, when I told him about my plans. "Seeing another person's toothpaste in the sink is pretty existential too," I said. That we used the word existential about such things tells you how young we were, not long out of school.

I couldn't crack the weird-roommate-riddle though. Not for a long while. Ken, as we'll call him, was a narcissistic artist, with more compulsions than toes, who shared David's large apartment for three years, in a moldering Victorian mansion. Each morning, sitting bolt upright in bed, he loudly recited his latest dream into a video cam. The furniture was arranged in a nutty shin-scraping fashion, because Ken believed that furniture wanted to be in certain places. Whenever I stopped by the apartment, one of Ken's many depressed girls was always in the kitchen, moodily eating cornflakes, dressed in one of his t-shirts. They came and they went, these girls, and I never knew their names.

Ken was a performance artist, one who ran around on all fours, mimicking animal movement, wearing a black stretch suit, using self-invented shock absorbers so he could lope along easily, like a dog or coyote. He nagged David into photographing him outdoors, doing his thing, which David hated but always acquiesced. Inevitably, a fearful passerby would call the police to report a huge black ape loose on the streets. When the squad cars came, Ken refused to say anything. He'd just trot around aimlessly on all fours, while David tried to explain performance art to a bunch of cops.

Eventually, Ken disappeared into a Bowery studio, where he may be to this day, for all I know. For years, David maintained a near saintly patience with Ken's vagaries just because he liked him. At least that's what I believe because it's so David-like. It may even be true.

The closest David and I ever came to a fight was ten years ago. Just wanting to hear his voice, with its welcome flat Pennsylvania accent, I called. We chatted about this and that, innocuously I thought, and then David asked very quickly, "So how does it feel to be a corporate sell-out?" There was real anger in his voice, an anger I'd never ever heard, and I was speechless, then felt a dangerous hot answering anger in myself.

But the better angel of my nature, a smallish angel to be sure, recognized the innocence in his question. David didn't know squat about global business and why should he? Gently, unlike me, I explained I'd wanted to know how consumer products got dreamed up, created,and manufactured. I'd been curious and went adventuring and that was all. "Oh," David said, his voice lifting with something like surprise. And then we were okay.

Later I thought how old friends become our parents if we don't watch out. Bewildered by our later choices, they wonder out loud, But the man you divorced was so perfect. And then you threw away your whole career, moving to that crime-ridden city?

Exasperated, you want to smack them in the head. That man I divorced was crazy, my career was a big zero, and my home town was a cracked-out Springsteen rust belt.

Your friends' questions are as unanswerable as those of aging parents, shouted over too a far distance. But like our mothers and fathers, our old friends are only asking, Do you remember me?

Sometimes, we can holler back, loudly and truthfully: Yes! Yes! I see you! I see you as you were. I see you as you are. I loved you then. I love you now.

If we're lucky, lucky dogs, that's what we can say.

No comments:

Post a Comment